First Murder: Genesis Story Reimagined in Speculative Fiction

Before history had a name, before kingdoms or kings, there were only a few families who tilled the soil, herded flocks, and learned by divine whisper how to live upon the earth. Among them were two brothers—Cain and Abel—whose story would become the first tragedy, the first reckoning, and the first reminder of how fragile the human heart can be.

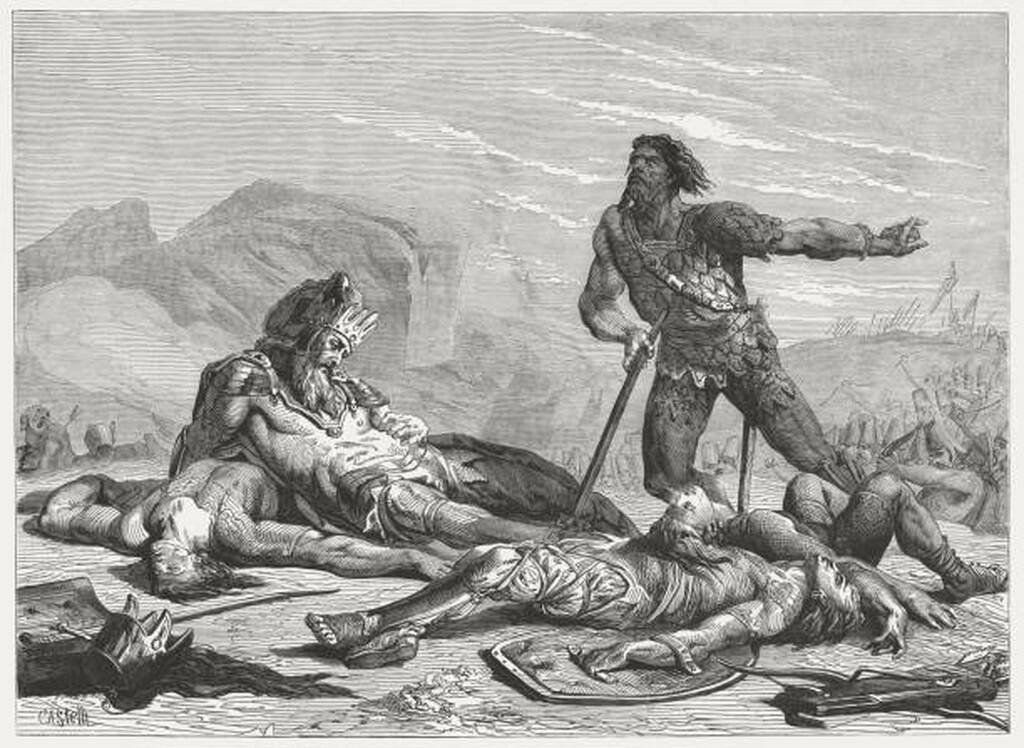

The tale of the first murder has echoed across centuries. Told simply in Genesis—one brother’s jealousy, one fatal act—it is a story so stark that its silences are louder than its words. Why did Cain truly kill Abel? Was it envy alone, or something deeper—a rupture between humanity and heaven itself? What happens when faith becomes silent, when love turns to law, and when obedience asks too much of the heart?

It’s in those silences that speculative fiction begins to breathe.

When I set out to write Cain, I wanted to enter the spaces Genesis leaves untouched—the inner world of the first sons, the family life of Adam and Eve, and the beginnings of a society struggling to understand divine justice. Drawing from apocryphal texts, early Jewish commentaries, and oral traditions, I found fragments of a larger, richer world. In these ancient writings, Cain is not merely a murderer. He is a visionary, a builder, a man torn between faith and freedom, between the God of his father and the whisper of a New God promising autonomy and power.

What fascinates me most about speculative fiction is its ability to reveal truth through imagination. It does not replace scripture—it explores it. It allows us to ask: What if the first murder was not only an act of rage, but a moment of cosmic rebellion? What if Cain Apocryphal Fiction marked the beginning of humanity’s restless search for meaning outside divine order?

In Cain, that search takes form in a world alive with mystery and consequence. The Watchers—angels sent to guide the first families—walk among mortals, observing their progress and their peril. Secret societies rise in the shadows, led by those who hunger for knowledge and independence. And in the midst of it all stands Cain—strong, brilliant, and flawed—caught between love for his sister, loyalty to his father, and the growing belief that heaven no longer listens.

The murder itself becomes more than a moment of violence—it becomes the fulcrum of human history. In killing his brother, Cain severs not only blood ties, but the bond between creation and its Creator. The ground that once yielded to his touch turns against him, and the echo of that act reverberates through all generations: the birth of exile, the weight of guilt, and the enduring question of redemption.

Speculative fiction gives voice to what the ancient texts only imply: that Cain’s rebellion did not end with Abel’s death. Cast out, he becomes the father of cities, the founder of systems built on secrecy, ambition, and power—the first architect of civilization without God. His mark is not merely a curse, but a warning and inheritance: that the human spirit, once unbound, will always wrestle with its maker.

In retelling the Genesis story through this lens, Cain becomes more than biblical fiction—it becomes a meditation on choice, consequence, and the cost of silence. It invites readers to look beyond judgment and into understanding, to see Cain not only as the first sinner, but as the first seeker—the one who dared to ask the unanswerable.

For me, the story of the first murder is not just about loss. It is about the beginning of everything that defines us: love, jealousy, freedom, guilt, and the endless yearning to be known by God.

Because every act of rebellion carries a shadow of hope. And every exile, no matter how far he wanders, still remembers Eden.